By Edward Ortiz, Sacramento Bee

When employees at technology giant Oracle sit down to lunch, they often eat produce grown in Yolo County’s Capay Valley.

The fruits and veggies come from the Capay Valley Farm Shop, which buys from more than 40 farmers in the valley and delivers to chefs that work in restaurants and institutional cafeterias, primarily in the Bay Area.

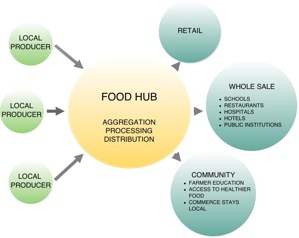

The Farm Shop is one of a growing number of food hubs that are giving farmers a new avenue to sell their wares – and allowing stores, restaurants and institutions to buy locally grown, fresh produce in bulk.

Farmer participation in food hubs is skyrocketing. U.S. Department of Agriculture data show the number of hubs in the United States has risen 288 percent since 2006 – to 302.

That increase outpaced the growth of farmers markets, which saw dramatic increases between 1996 and 2012. From 2013 to 2014, the number of farmers markets only grew 1.5 percent. In 2012-13, the increase rate was 3.6 percent.

So many farmers markets have been added, they may have reached a saturation point, said David Shabazian, project manager at the Sacramento Area Council of Governments. Shabazian recently co-authored a SACOG feasibility study for a larger regional food hub.

Food hubs appeal to farmers because they offer the opportunity to sell much larger quantities compared with farmers markets. That’s because food hubs typically sell to corporations and institutions, not consumers. Large food-distribution companies typically don’t buy from individual farmers, so food hubs present a new opportunity to crack the commercial market.

Schools, for example, are increasingly embracing the idea of buying locally grown produce. In 2014, trustees for the California State University system approved a policy that at least 20 percent of all campus food spending by 2020 will go to local farms and businesses. The University of California system last year announced the UC Global Food Initiative, which will explore ways to allow local growers to become campus suppliers.

Shabazian said he believes the food hub is a good vehicle to make sales to such entities possible.

Thomas Nelson agrees. He is the president and co-founder of the Capay Valley Farm Shop. “Getting product to market five days a week can be a challenge for most farms,” said Nelson, whose trucks travel daily to the Bay Area and weekly to Sacramento.

Participation in the Capay food hub has proved a market expander for the 350-acre Full Belly Farm in Guinda, said co-owner Judith Redmond. Full Belly employs 70 people and operates year-round, growing vegetables, fruits, flowers, herbs and meat.

Each day the farm accepts orders from 30 to 40 restaurants, stores and wholesale distributors, and delivers them through the food hub. Full Belly products have ended up at institutions like Oracle and the food-delivery website Good Eggs.

To reach such customers on its own, Full Belly would have to drive trucks into San Francisco, which would be costly and time-consuming, Redmond said.

At Cafe 300, which is located in Oracle’s large campus in Redwood City, chef Armando Maes has been making good use of Full Belly products.

“The Capay Valley Food Hub is great because it allows me to buy unique ethnic items that you would not be able to get otherwise, such as as okra, hops, rare heirloom vegetables native to those areas that dot the Capay Valley,” Maes said.

In Sacramento, the Capay Valley food hub delivers to restaurants like Mulvaney’s B&L and also to institutions like the California Department of Public Health.

At the moment, there is no established food hub in Sacramento. But SACOG’s feasibility study concluded the idea could work here.

“This is not a leap of faith. The analysis found a food hub will be a profitable venture, but it will take some time to get there,” Shabazian said. “In 10 years, it should be making about $2 million a year,”

He said he thinks the region is well positioned for a hub given that there is a port, rail and four major highways that traverse the region.

SACOG envisions an operation that would be much larger than the one in the Capay Valley and would cost $6.9 million to build. The regional government body is working to line up financing.