By Kathleen Merrigan, former USDA deputy secretary and current director of the Swette Center for Sustainable Food Systems at Arizona State University

Organic food once was viewed as a niche category for health nuts and hippies, but today it’s a routine choice for millions of Americans. For years following passage of the Organic Foods Production Act of 1990, which established national organic standards, consumers had to seek out organic products at food co-ops and farmers markets. Today over half of organic sales are in conventional grocery store chains, club stores and supercenters; Walmart, Costco, Kroger, Target and Safeway are the top five organic retailers.

Surveys show that 82% of Americans buy some organic food, and availability has improved. So why do overall organic sales add up to a mere 6% of all food sold in the U.S.? And since organic farming has many benefits, including conserving soil and water and reducing use of synthetic chemicals, can its share grow?

One issue is price. On average, organic food costs 20% more than conventionally produced food. Even hardcore organic shoppers like me sometimes bypass it due to cost.

Some budget-constrained shoppers may restrict their organic purchases to foods they are especially concerned about, such as fruits and vegetables. Organic produce carries far fewer pesticide residues than conventionally grown versions.

Price matters, but let’s dig deeper. Increasing organic food’s market share will require growing larger quantities and more diverse organic products. This will require more organic farmers than the U.S. currently has.

There are some 2 million farms in the U.S.. Of them, only 16,585 are organic – less than 1%. They occupy 5.5 million acres, which is a small fraction of overall U.S. agricultural land. Roughly two-thirds of U.S. farmland is dedicated to growing animal feed and biofuel feedstocks like corn and soybeans, rather than food for people.

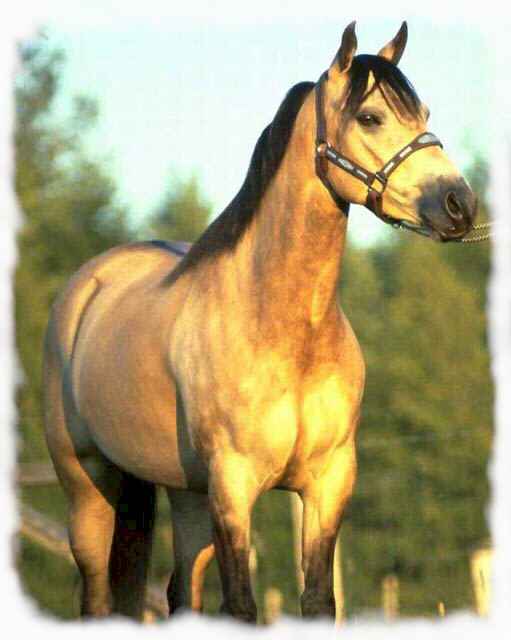

In my view, converting more agricultural land to organic food production should be a national goal. Organic farmers produce healthy food, promote soil health and protect watersheds. Ruminant animals like dairy cows when raised organically must graze on pasture for at least 120 days each year, which reduces their methane emissions.

The list of climate and environmental benefits associated with organic is long. Organic farming consumes 45% less energy than conventional production, mainly because it doesn’t use nitrogen fertilizers. And it emits 40% less greenhouse gases because organic farmers practice crop rotation, use cover crops and composting, and eliminate fossil fuel-based inputs.

The vast majority of organic farms are small or midsized, both in terms of gross sales and acreage. Organic farmers are younger on average than conventional farmers.

Starting small makes sense for beginning farmers, and organic price premiums allow them to survive on smaller plots of land. But first they need to go through a tough three-year transition period to cleanse the land.

During this time they are ineligible to label products as organic, but must follow organic standards, including forgoing use of harmful chemicals and learning how to manage ecosystem processes. This typically results in short-term yield declines. Many farmers fail along the way.

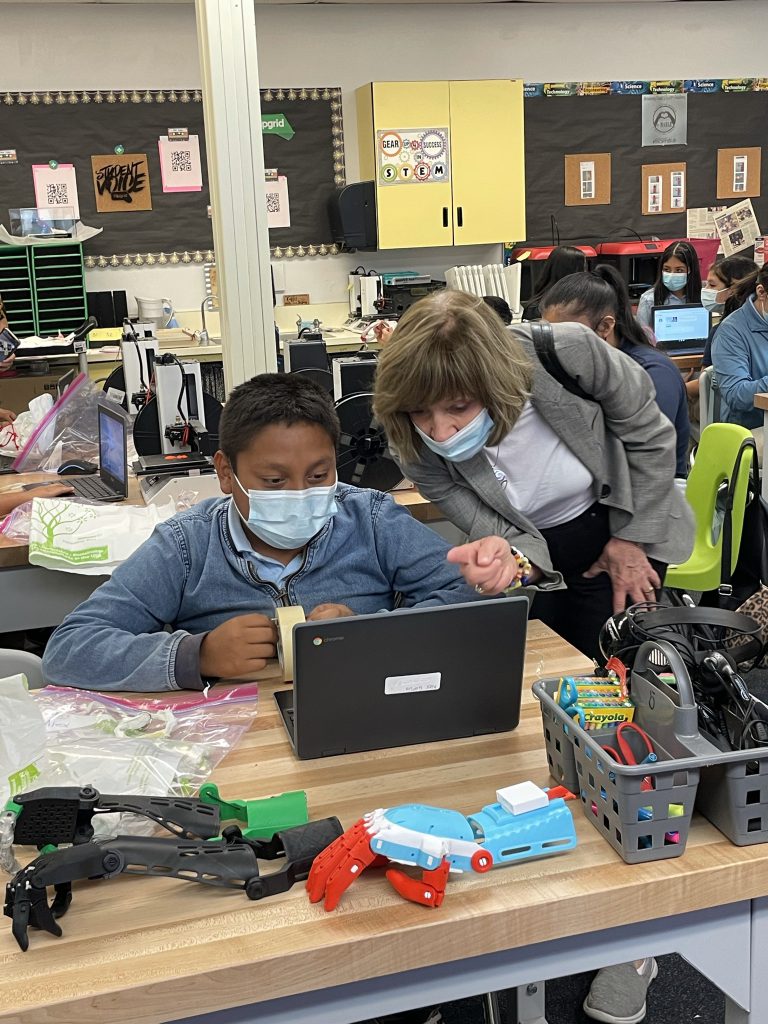

The transition period is just one of many challenges for organic farmers. Greater federal government support could help. In a recent report, Arizona State University’s Swette Center for Sustainable Food Systems, which I direct, identified actions the Biden administration can take within existing budgets and laws to realize the untapped promise of organic agriculture.

Current USDA assistance for organic producers is paltry, especially given the billions of dollars that the agency spends annually in support of agriculture. Two-thirds of farm subsidy dollars go to the top 10% richest farms.

Our report recommends dedicating 6% of USDA spending to supporting the organic sector, a figure that reflects its market share. As an example, in 2020 the agency spent about $55 million on research directly pertinent to organic agriculture within its $3.6 billion Research, Education and Economics mission area. A 6% share of that budget would be $218 million for developing things like better ways of controlling pests by using natural predators instead of chemical pesticides.

Organic food’s higher price includes costs associated with practices like forgoing use of harmful pesticides and improving animal welfare. A growing number of food systems scholars and practitioners are calling for use of a methodology called True Cost Accounting, which they believe reveals the full costs and benefits of food production.

According to an analysis by the Rockefeller Foundation, American consumers spend $1.1 trillion yearly on food, but the true cost of that food is $3.2 trillion when all impacts like water pollution and farmworker health are factored in. Looked at through a True Cost Accounting lens, I see organic as a good deal.

Link to story on The Conversation web site

Visit this page to view CDFA’s 2019-2020 Organics Report