From the California Milk Advisory Board:

New study conducted by University of California Agricultural Issues Center shows significant impact of state’s leading agricultural commodity

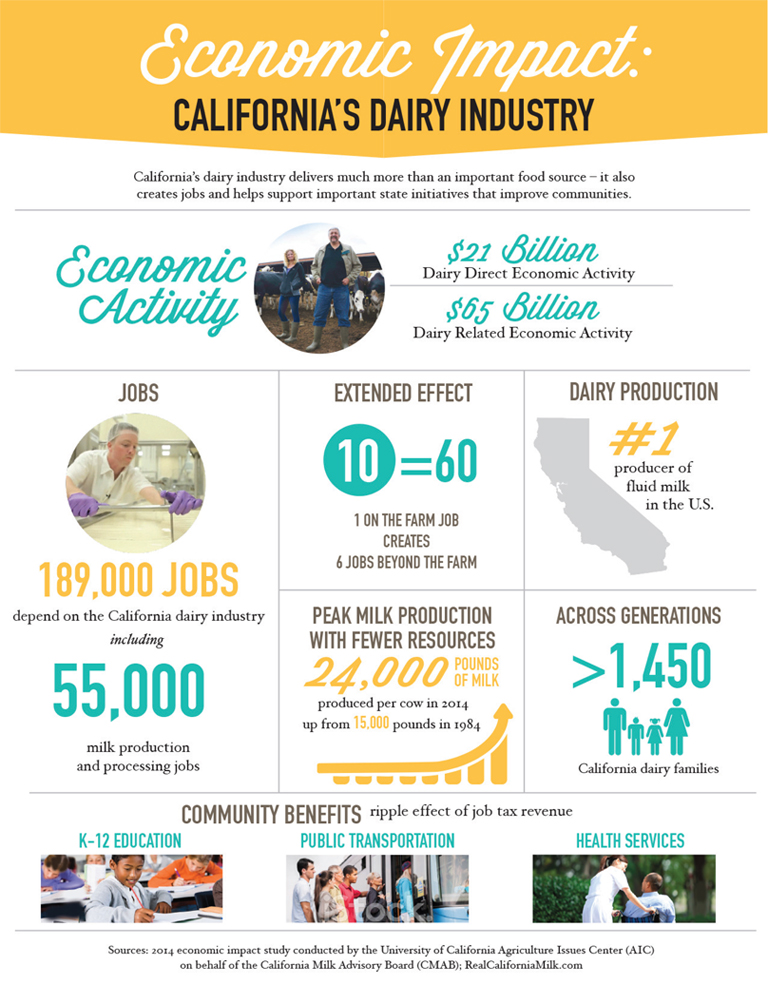

Cementing its place as California’s most important agricultural commodity by farm revenue, California farms sold about $9.4 billion worth of milk while the dairy industry contributed approximately $21 billion in value added to the gross state product in 2014, according to a California Milk Advisory Board (CMAB) study conducted by the University of California Agricultural Issues Center (AIC). Including sales of inputs to dairy farms and milk processors along with raw milk and wholesale milk product sales, the dairy industry contributed $65 billion in total sales to the California economy in 2014. The growing demand for dairy products like cheese and yogurt as well as strong dairy exports accounted for 189,000 jobs that are dependent on the state’s milk production and processing.

“The dairy industry’s contributions are vital to California’s economy, from creating jobs to stimulating local and regional economies to providing nutritious and enjoyable products to consumers everywhere,” said John Talbot, CEO at the California Milk Advisory Board. “A large number of California residents depend on the dairy industry for employment and these jobs would not exist without it.”

The $21 billion to California’s gross state product included $7.4 billion as income to industry workers and owners and $13.4 billion through related, outside industries such as feed, veterinary and accounting services used for dairy production and electricity, packaging, equipment and trucking services used by processors. The tax revenue generated from these jobs supported important statewide initiatives to improve education, healthcare, roads, community services and the environment.

Overall, 189,000 jobs in California are associated with the dairy industry. Of this amount, approximately 30,000 jobs are on the farm and 20,000 jobs represent dairy processing. For every dairy farm job, there are several more jobs that are tied to the business and create a linked chain of economic impacts.

Additionally, the induced effect of the dairy industry also creates jobs in the community to support the area’s dairy workers and their families, such as school teachers and local bus drivers.

California Holds Rank as Nation’s Dairy Leader

California leads the nation in dairy production and dairy continues as the top commodity in the country’s top agricultural state. It has been the nation’s largest milk producer since 1993 and is also the country’s leading producer of butter, ice cream, nonfat dry milk and whey protein concentrate. California is also the second largest producer of cheese and yogurt.

Farm milk sales generated $9.4 billion gross revenue in 2014. Wholesale dairy product (cheese, fluid milk, ice cream, butter and other dairy) sales hit $25 billion in 2014.

Dairy Farmers Improve Business Performance

As an essential part of California’s farming heritage, dairy farmers understand the importance of protecting the land, water and air for their families, their communities and future generations. In 2014, California dairy farmers produced more milk with fewer resources. Talbot credits “improved dairy practices and management adopted by farmers” for the increased business efficiencies. The pounds of milk produced per cow increased to 24,000 pounds in 2014 from 15,000 in 1984. Farmers are applying 23 percent less water to their fields than they did in the early 1980s and have seen their average crop yields increase by more than 40 percent despite using less water.

Beyond the economic impacts calculated in the report, California dairy farmers and employees are active participants in their communities and contribute to social, environmental and other broad public goals.

Study Leaders and Methodology

The study was conducted by a team of researchers at the University of California Agricultural Issues Center (AIC). Daniel A. Sumner, the director of AIC who holds the Frank H. Buck, Jr. Chair Professorship in the department of Agricultural and Resource Economics, UC Davis, led the study. Josué Medellín-Azuara, a project scientist at the UC Davis Center for Watershed Sciences, and Eric Coughlin, a junior research specialist at AIC, were part of the research team. They measured myriad impacts using dairy-specific data for 2012 and projections for 2014 and a database and model of economic linkages (IMPLAN).

About the California Milk Advisory Board

The California Milk Advisory Board (CMAB), an instrumentality of the California Department of Food and Agriculture, is funded by the state’s more than 1450 dairy families. With headquarters in South San Francisco and Modesto, the CMAB is one of the largest U.S. commodity boards. It executes advertising, public relations, research and promotions on behalf of California dairy products, including Real California Milk and Real California Cheese. For more, visit RealCaliforniaMilk.com.

See the original press release on CMAB’s site here.

A summary and links to the full report are available here.