By Amber Manfree

In the historic heart of Napa Valley, a moderate climate and the alluvial soils deposited by the Napa River create perfect conditions for world-class cabernets. An acre of vines here sells for around $300,000, or 25 times the state average for irrigated cropland.

Yet a group of landowners have ripped out 20 acres of these prized vineyards to make room for river restoration, with levee setbacks, terraced banks and native plants.

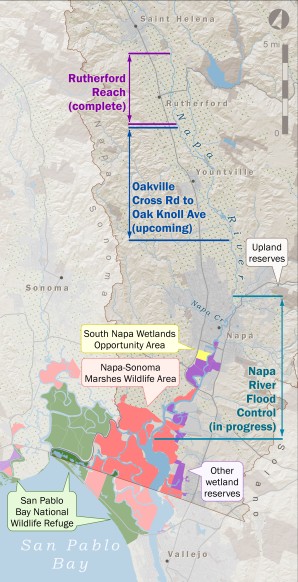

The project runs the length of Rutherford Reach, a 4.5-mile stretch of the Napa River between St. Helena and Oakville. Landowners say the changes will bring economic benefits over the long term by reducing crop losses from floods and plant disease. Most of all, they feel good about giving back to the river that has brought them so much.

Rutherford Reach is one several sites undergoing major habitat and flood control improvements on the Napa River. Some projects started more than 40 years ago. Others are just getting off the ground.

Far from postage-stamp restorations, these efforts are steadily transforming a huge swath of wetlands in a very lived-in rural area, re-establishing geomorphic function at the landscape scale.

Innovative funding, inclusive planning and adaptive management power these projects and offer lessons for river restoration elsewhere.

For decades, landowners along the Rutherford Reach struggled with bank instability and floods. The river was confined to create more space for vineyards while upstream dams reduced sediment delivery, leading to incision and eventually lowering the riverbed six to nine feet.

Without a healthy stream profile, desirable river processes and species were lost. Invasive plants such as giant reed and Himalayan blackberry overtook the banks, further degrading habitat and hosting problem insects.

Then, in 2002, a group of influential vintners organized as the Rutherford Dust Society approached Napa County about partnering to restore the reach, and a new path to restoration unfolded. The landowners:

- Led the initiative and were involved throughout the planning process

- Are making meaningful contributions of land and money

- While motivated in part by economic considerations, they find conservation to be its own reward

More than two dozen landowners support the $20 million restoration and its long-term maintenance, each paying an annual fee based on the linear feet of river crossing their property. Altogether, the landowners will contribute about $2 million over 20 years. The project also is supported with $12 million from a county bond measure and $7.7 million in state and federal grants.

County staff have spent 10 years monitoring the transition from degraded to restored riparian corridor, revising techniques as they go. If something isn’t working – invasive weeds are popping up, a log jam blocks fish passage, an herbicide kills non-target species – the corrections can be made in the field, and landscape processes continue in the intended direction instead of backsliding.

With the first 4.5 miles of riparian corridor construction wrapping up, project managers are preparing to restore 9 more miles just downstream between Oakville Cross Road and Oak Knoll (See map). Together, these projects will transform habitat along 25 percent of the river’s 55 miles.