by Jay Lund

Agriculture is California’s predominant use of managed water. Agriculture and water together are a foundation for California’s rural economy. Although most agriculture is economically-motivated and commercially-organized, the sociology and anthropology of agriculture and agricultural labor are basic for the well-being of millions of people, and the success and failure of rural, agricultural, and water and environmental policies.

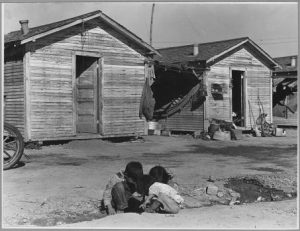

The economic, ethnic, and class disparities and opportunity inequalities in urban life are urgent problems today. Similar problems continue to exist in the structure of rural communities. These rural problems often are more dire and difficult because the lower densities of rural settlement make these problems harder to observe, bring greater difficulties for organization, information, and logistics, and increase per-capita expenses for actions that provide services (water, education, transportation, housing, and all manner of human services). The anthropologist Walter Goldschmidt observed these difficulties in California’s San Joaquin Valley in the 1940s (as John Steinbeck did in the 1930s).

Most serious social scientists and policy wonks of California agriculture (and agriculture in general) have read Walter Goldschmidt’s As You Sow (1947). Those who haven’t should.

Despite decades of subsequent research, much of this work could be written and read insightfully today, and it retains much influence, as seen in Mark Arax’s recent history of California’s water development (2019).

Some, of many, points made in Goldschmidt’s book include:

- History, expectations, and economic structure have implications for local social structure and the experience and opportunities of people individually and as social groups. The San Joaquin Valley’s social structures arose and arise from a history of demographic, economic, and social transitions built around migrations, farming, and perceived economic opportunities. Goldschmidt discusses how these transitions often involved efforts to limit opportunities for some groups, particularly individuals and groups providing farm labor.

- The book is a nice example of a fairly classical anthropological/ethnographic approach to studying social structure and public policy issues, showing how social scientists have long produced insightful results for policy problems, in this case on social, economic, and policy implications of modernization in agriculture and the urbanization of agriculture and rural life. (Feel free to comment on this post with citations and links to additional great examples – a few appear under further reading.)

- The original presentation of what became the “Goldschmidt hypothesis,” that areas dominated by family farms tend to have more desirable socioeconomic conditions than industrial farming areas. This idea has been both supported and not supported by many more recent studies (cited under further readings), and might be less relevant today as remaining commercial family farms have grown in industrial scale since the 1940s.

- The importance of effective local social and governmental organization and expectations for providing good schools, social services (human services, police, etc.) and infrastructure services (water, sewer, transportation, housing, energy, and solid waste). This applies for everyone, everywhere and at all times, I think.

- Fundamental objectives of policy – these seem eternal and relate to more than just rural and agricultural policy (p. 254): “Three fundamental principles must underlie any constructive farm policy consistent with American democratic tradition:

- The full utilization of American productive capacity to insure the welfare of all the people and the strength of our nation;

- The preservation of our national resources to insure that maximum production can continue without loss from earlier exploitation of the land;

- The promotion of equity and opportunity for those whose life work is devoted to the production of agricultural commodities.”

- One footnote I enjoyed were references to the scholarly work of Clark Kerr on farm labor and policy in the 1930s. Clark Kerr went on to oversee the progressive transformation of the University of California in the 1960s as UC President.

This is another great book on California, agriculture, and water (one of many). It nicely focuses on people, and some of the most economically and socially underprivileged people in California, then and now. These places, and their like, still exist with social and economic structures that affect human health, well-being, and water management (Ramsey 2020). Struggles to better achieve the universal political and economic objectives summarized by Goldschmidt in 1947 continue.

Considering people in agriculture is among the hardest and most central issues as California works to adapt agriculture to reduce groundwater overdraft and contamination, manage the Delta more sustainably, improve rural water services, protect ecosystem health, and improve rural life and opportunities.

As I read recently, “Read old to stay sharp.” And then read some more.

Jay Lund is a Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering at the University of California – Davis.

See the original post on California WaterBlog.

One Response to People, Agriculture, and Water in California – from California WaterBlog