Rising costs of compliance are forcing many growers to switch crops, shut down or leave the state

By Tim Hearden

Dairy owner Steve Nash used to be enmeshed in California politics, staying active in the Fresno County Farm Bureau and appearing before state legislators and regulators to advocate for agriculture-friendly policies.

But in 2014, he gave up. He began the process of moving his business from Selma, Calif., where it had been operating for more than 80 years, to Chapel Hill, Tenn.

“Milk was at one of its lowest prices in California at that time, and we were looking at the Southeast and their marketing order,” Nash said.

He scouted out land from Arkansas to Georgia and settled on Tennessee “because of the business climate and their ag department,” which helped him search for properties, he said.

Today his family raises 1,350 cows – mostly Holsteins and some jerseys – on 700 acres in a little farming community south of Nashville. He has about 200 more cows and farms about 100 more acres than he did in California.

Tough decisions

“Regulations were probably one of the biggest” reasons for leaving the Golden State, Nash told Farm Press. “We wanted to build and expand, and there was a lot of cost to doing that – everything from environmental impact reports and assessments to things as small as the fire department being involved in the expansion of your dairy. Everyone wanted a fee.”

Nash is one of many growers who’ve been forced to make some tough decisions about their California operations in recent years as the state has imposed a morass of red tape in the areas of water and air quality, food safety, labor wages and worker health and safety.

New regulations since 2006 have caused significant increases in growers’ cost of production, making it more difficult for all but the biggest farms to survive, noted researchers at California Polytechnic University, San Luis Obispo in a 2018 report.

Some growers are left with an ominous choice: switch crops, move out of California or quit farming altogether.

“I’ve always said there’s not a single regulation per se that’s going to undo the farm in California, but it’s a death by a thousand cuts,” said Ryan Jacobsen, the Fresno County Farm Bureau’s chief executive officer. “There are so many pressing issues at one time.

“The biggest issue right now is water,” including new pumping restrictions under the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act, Jacobsen said. “But there are other issues that make it difficult to continue to farm in a state when we’re still competing on a global landscape.”

Ag receding

As new laws and restrictions are added every year, agriculture has been receding in California. Though it still leads the nation in production, the state lost more than 1 million acres of farmland and some 7,000 farms from 2012-2017, according to the USDA’s latest Census of Agriculture.

The state’s cattle and calf inventory declined during the period from 5.4 million to 5.2 million, as the number of ranches fell from 16,764 to 13,694, and the number of dairy farms continued a trend of declines over the last two decades, driven partly by lagging whey prices that prompted farms recently to join the national marketing order.

Grain acreage in California has cratered, with corn and wheat farms and acreage cut in half, according to the census. Rice acreage declined from 531,075 acres in 2012 to 436,710 in 2017 amid water shortages that often affected the timing as well as the amount of deliveries.

Some farmland has been converted to other uses. From 2001-2016, 316,600 acres of California’s agricultural land were converted to urban and highly developed land use, while another 149,400 acres of the state’s farmland were converted to low-density residential, according to a recent study by the American Farmland Trust. The state has about 24.3 million total agricultural acres.

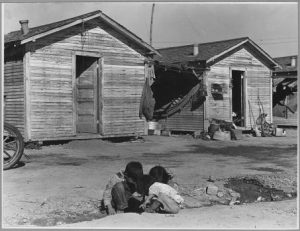

In many instances when a farm is closed or moved, the land is simply sold to a larger operation that has the wherewithal to take on the costs. If the trend continues, by 2030 there will be less acreage in fewer hands with fewer crops grown.

“It’s becoming more and more difficult for particularly smaller and medium-size operations to continue to farm with very few crops offering a level of return … to continue to stay in business when the farm returns continue to diminish and the outlook on most crops is not necessarily the brightest,” Jacobsen said.

“For the most part, a lot of commodity prices are on the more depressed side, yet we don’t have any kind of relief coming from the regulatory front,” he said. “It’s becoming more and more difficult for small and mid-size operations to stay viable.”

Asparagus disappears

On many farms, water cutbacks, higher costs or paperwork burdens have led to changes in cropping patterns, which have decimated once-abundant commodities such as cotton and asparagus. Jacobsen calls the asparagus industry “a bellwether” in terms of how changes in minimum wage and overtime laws are making some crops cost prohibitive.

In 2007, California growers harvested 58 million pounds of fresh asparagus from 20,000 acres. That fell to just over 20 million pounds of production from 8,000 acres in 2016, according to the California Department of Food and Agriculture.

Competition from Mexico is the primary reason for the decline, which prompted the state’s remaining growers to suspend activities of the California Asparagus Commission at the end of last year.

As California acreage shrank, states like Michigan and Washington have increased production, according to USDA figures. Joe Del Bosque, owner of Del Bosque Farms in Firebaugh, Calif., is still growing asparagus, but his acreage has been cut in half because foreign competitors can ship fresh asparagus into California cheaper than he can produce it, he said last fall.

Del Bosque began growing certified organic asparagus several years ago to improve margins, but there’s competition from Mexico in that arena, too, he said.

As growers in California switch to other vegetables, it creates “a domino effect” that pushes the other crops into surplus and depresses prices, Jacobson said.

“The great strength of California agriculture is our diversity,” but that’s changing as other parts of the world gain competitive advantages, he said.

For many, the solution has been to join – or redouble their efforts in – the ever-burgeoning tree nut industry. Winters Farming Co. shut its 1,300-cow dairy in Oakdale, Calif., two years ago and is focusing on its almond, walnut and grape plantings on several farms in the Central Valley.

The operation sold its 750 milking cows to a dairyman in Utah, while the calves and heifers were sold to a producer in Kansas, farm manager Alex Bergwerff said.

‘A losing battle’

“Primarily you’re running a losing battle” by operating a dairy in California, he said. “Just in the last decade or 20 years, there would be years that were really, really good and you could pay down a lot of debt, but that seemed to be a declining trend in the last 5 or 6 years.

“My dad and uncle were getting older and didn’t need that stress,” he said.

Bergwerff notes that many Dutch immigrants settled in the northern San Joaquin Valley and started dairies years ago, and now many of the families have shut down or moved. A friend of his father’s moved his operation to South Dakota, he said.

“The thought in California that ag is not environment-friendly is scary,” Bergwerff said. “People really think that ag is not up to date in technology, but they’re working to do their best.

“It seems like with whatever market is making the most money, the socialistic idea is to go after that market, and that scares me,” he said. “I would like to see ag as a whole thrive in California. It’s such good weather and a good economy, and people can make a good living out of it.”

Note: this piece is part of a series of articles by Western FarmPress examining what California agriculture could look like in 2030 – a decade from now. Read the original article on the Western FarmPress site.