California State Board of Food and Agriculture president Craig McNamara (far right) in New Yavne, Hamerkaz, Israel.

Secretary Ross is traveling through Israel this week with a California delegation interested in adaptation strategies for climate change and drought

Yesterday we started with an excellent overview of agriculture in Israel presented by Oren Shaked, a senior agricultural specialist with the U.S. Embassy. Oren described water in ag like a bike ride, “you can never stop pedaling!” They continually look at how they can do more with every drop they get. He noted the Field Advisory Service of Israel plays a vital role in the adoption of ag technology.

The list of challenges facing farmers here was almost identical to a list for California with the exception of BDS (boycott divestment sanctions). We heard about real world effects of BDS later in the day from a young farmer who has suffered loss of markets in the EU.

Our meeting with Mekorot, Israel’s National Water Company, was fascinating and could have easily lasted a half day! The Israel Water Commission makes the decisions on all water allocations and pricing. Waste water is a resource and water for ag is priced by type of treatment. Mekorot is the engineering and knowledge mechanism for its delivery. Mekorot’s 30 years of experience in seawater and brackish water treatment has improved energy efficiency, reduced consumption of chemical products, and minimized water loss (to leakage and evaporation). Mekorot prides itself on being a world leader in water technology that has turned an arid desert into a “flowering garden,’ and seawater into drinking water.

The Volcani Institute, the research arm of the Ministry of Agriculture, has 200 scientists, 800 support staff and 300 students working on a broad agenda with a focus on arid-zone agriculture in a changing climate. We heard about their special wheat breeding program to develop varieties to cope with climate change; efforts to combat the impact of rainfall on soil erosion and run-off; lysimeters used to study plant nitrate uptake and deep percolation for different water qualities and crops; the use of plant sensors to measure water flow in citrus trees as well as stem growth and contraction; thermal imaging and drones to detect real time irrigation needs; automatic traps to monitor pests and real time changes in their behavior; and, new technology that enables simultaneous temperature and humidity control in greenhouses for optimal yield production.

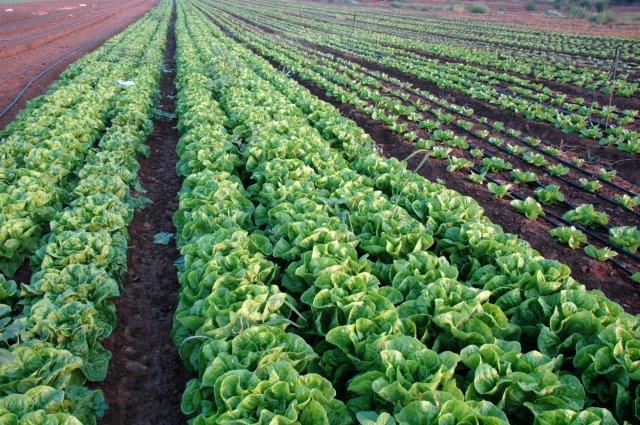

Our last stop of the day was at Hishtil Ashkelon, a family business started in 1974 to provide premium plants to produce growers in hot climates. The company is GLOBALG.A.P.– certified and adheres to strict protocols for uniform, reliable plants. Its grafted plants are suited for mechanical planting.

The evening ended with sunset on the Mediterranean and a fun dinner in old-town Jaffa. I am traveling in great company!

The California Climate-Smart Agriculture Policy Mission is funded in part by the California Department of Food and Agriculture’s Specialty Crop Block Grant Program